The Tea Production Process

How the Harvested Tea is Processed and Refined into the Drink We Enjoy.

This is the third of our series on Japanese tea production, from the plant, through its cultivation to the final product, the tea we like to drink.

At this point in the tea-making process, the plant has been selected, planted, grown and cared for. The tea has been harvested, and it sits ready for processing.

When tea was introduced in Japan in the 9th century from China, it was always prepared by pan-firing the leaves and grinding. In some of the earliest books on tea and tea accessories, the tea grinding wheel was always prominent. and the prevalence of loose-leaf tea in Japan did not appear until centuries later.

Like everything that has evolved over time, the production methods used are varied, not set in stone, not even a grinding stone. There are many variations, and we will cover just the main steps, always bearing in mind that particular farmers and producers will have their own quirks or special tricks to get the best out of the plant. The tea-making process is a complex knitting together of lots of different choices, requirements, skills and innovations. It is what makes trying different tea and discovering nuances amongst different tea types (Sencha from Gyokuro) but also between different versions of the same type (Sencha from one farm or region versus another) so fascinating.

This discussion is quite long and detailed, so we advise you to grab a cup of your favorite tea and get comfortable.

Tea Production Process

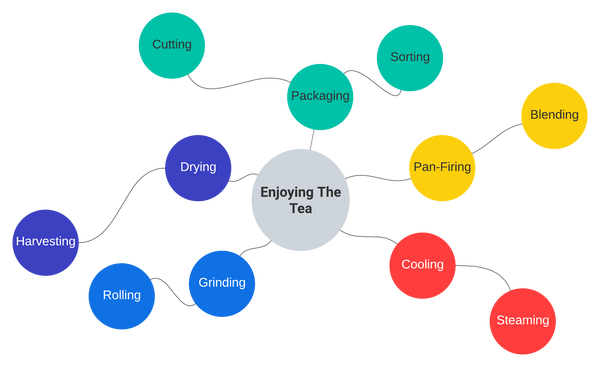

We can break the steps down the production process into two stages, the primary steps, called Aracha and the secondary steps, called Shiagecha.

The tea production process is focused on stopping the tea from oxidizing, getting water out of the tea, and softening and shaping the tea so that it is a shape and texture that can quickly impart its flavor to the water when it is prepared.

If one were to do the process by hand and had the expertise and equipment to perform the steps, it would take a whole day to go from picked tea to the finished product ready for drinking – there would be many steps and some vigorous work involved. The volume of the finished tea in relation to the volume of the initial leaves would also be greatly reduced. One needs a lot of tea leaves to produce a relatively small amount of finished tea, so as we would expect, the production process is focused on getting the best-finished product from the raw ingredient.

All processing used to be performed manually but now is mostly done using machines. On our visits to farms and tea processors, we are always amazed by the ingenuity of the array of machines that are used to perform the various steps; modern machines now utilize things like color-sensitive electronics that can separate leaves from stems, but the real fascination for us are the mechanical machines, like Rube Goldberg machines, that have been developed over the years to directly mimic the human movements using wheels and gears and belts and numerous other mechanical parts.

There are many different types of tea in Japan. We have the famous Sencha that makes up the majority of the production. We have Hojicha and Genmaicha, which can be considered Sencha derivatives in some ways. We have premium teas like Matcha and Gyokuro. We have newcomers and teas making a comeback, like Oolong and black teas which in Japan are referred to as Oolongcha and Wakocha.

All of these teas go through some or all of the processing steps outlined below.

Aracha - The Primary Processes in the Production of Japanese Tea.

Aracha is also the name given to a specific green tea. It is sometimes called farmer’s tea or crude tea because it is ‘rough’; it is produced as a result of the steps in the Aracha Stage and is the least processed of the Japanese teas. Aracha tea contains all of the tea parts before they have been separated, leaves from stems; for example, it has an earthly, unrefined taste that appeals to some tea drinkers. We occasionally have Aracha for sale at Chado Tea House.

Steaming.

As soon as the tea is picked, it starts to oxidize. The picking process, no matter how gently and carefully it is performed either by hand or by mechanical means, damages the cells within the leaves. The damage causes the release of polyphenols and enzymes that cause oxidation. The primary indication that oxidation has taken place is a change of color from green to brown.

Because the aim of Japanese tea producers is to produce green, fresh-tasting tea, the production process needs to prevent this oxidation. The method used is to heat the tea. In China, most tea is pan-fired or roasted. In Japan, the vast majority of the tea is steamed. The steaming of tea is almost ubiquitous in Japan and is the main differentiator between Japanese green tea and teas from other countries, where steaming, if it exists at all, is less utilized.

Japan imported tea from China in the ninth Century, and the heating process is fundamental to the tradition, so it is interesting to examine why the heating methods have evolved differently. It is thought that the Japanese were focused on preserving the natural flavor and fragrance of the leaves; this is best achieved by steaming. In China, the focus was on developing deep, complex flavors; these complex flavors could be developed more readily using roasting or pan-firing techniques. Teas like the Japanese Hojicha take advantage of both methods, the steaming to preserve the freshness and the pan-firing to add complex roasted flavor.

The steaming process stops oxidation it also removes the agricultural aroma of the cut tea – the aroma of finished tea is extremely important, and the production process is not designed to make the tea without the aroma; however, the smell of cut tea is strong and grassy, and the steaming process tempers it.

The steaming process is quick; it varies in duration but is less than 3 minutes; some teas are only steamed for 30-40 seconds. The length of steaming is a very important step in the production process, and the length of time affects not only the oxidation process but also the final product’s taste.

The actual steaming involves loading the harvested tea into steaming machines, the leaves, stems and buds of the tea are all steamed. It is important to carry out the steaming process quickly after the tea is picked so no sorting of the tea is performed prior to steaming. The steaming process is the least refined of the processes that the tea will go through during its journey from harvest to finished product; often, the steaming location is adjacent to the fields the tea is growing in so it can be accomplished as quickly as possible. The process opens the ‘pores’ on the leaves and softens them to be more amenable to later processing steps, particularly rolling.

The steaming process is sometimes referred to as ‘fixing’ and describes how the enzymes in the tea that cause the decolorization is denatured – the enzymes are basically altered so as not to produce oxidation.

Water boils and produces steam at 100°C/212°F however if pressure is applied to the vessel where the water is heated, the water boils at a higher temperature and thus, the steam is hotter – Benifuuki tea tends to be steamed under pressure, but some producers will steam sencha for example at a higher temperature if they feel it adds to the finished product in some way - this is the type of variation that exists at almost every stage in the production process.

A classification of standard steaming times exists and is presented here.

Cooling.

After the tea is steamed, it not surprisingly heats up - we need to cool it down to stop the heat from ‘cooking’ the tea. Cooling down maintains the color, taste and aroma of the tea. The tea is typically allowed to cool on boards or tables; sometimes, cold air is blown over the tea. The cooling process also helps the excess water evaporate.

Rolling.

Rolling the tea has two main purposes. Firstly, the rolling process aids in the evaporation of some of the remaining moisture in the tea. The moisture comes not only from the steaming process above but also from the tea itself and the climate when harvested. The tea is rolled in large drums, and as it is agitated by these rotations of the drum, the moisture is removed.

The rolling process also allows the tea leaves to take on the needle-like shape we see in some finished teas like Sencha. The leaves are ‘rolled up’ over themselves to produce the shape. Not all tea in Japan is rolled into needle shape, but in those teas, like Gyokuro, for example, the rolling process still occurs but has the effect of making the tea have a flattish or even curled shape. The curled shape of some teas is especially prevalent in Japanese black teas. Wakocha, for example, is a black tea that is being produced in moderate volumes at the moment in some farms and is gaining popularity.

The Rolling machines perform many individual steps that used to be carried out by hand. The whole rolling process consists of kneading, straightening, rolling and drying. It is the longest process even now in the tea production process and involves vigorous manipulation of the tea. Prior to mechanical aids, I think it is a fair assumption that workers that were employed in the tea rolling process had to work very hard for their pay. If ever you do get a chance to see it done by hand, it is not only lengthy, intricate and skilled but also muscle-straining. There is a renewed interest in hand-rolling tea and hand-processing tea in general in Japan, and it is certainly worth checking out if you happen to be in Japan and a ‘community hand pick’ or a demonstration of the techniques used coincides with your travels.

Almost all Japanese tea is rolled, powdered tea, most notably Matcha, is not rolled as it will be ground later in production.

Drying.

After rolling, the tea is allowed to dry further. As mentioned earlier, the tea contains a lot of moisture and the processes the tea goes through reduce this water at each step. Approximately 95% of the water is removed from the tea when it enters the production cycle to when it is packaged and ready for brewing.

Shiagecha - The Secondary Processes in the Production of Japanese Tea.

The tea has gone directly from being picked through steaming, cooling, rolling and drying. Now is the time to separate the leaves from the rest of the plant and perform any special steps – for example, pan-firing or grinding.

Sorting.

Sorting is the first process that is optional; some tea is sold with all the parts of the plants included, for example, stem tea or Kukicha. For tea destined for that market, no extensive sorting is required. For tea that will be loose-leaf, the stems and buds usually need to be removed from the leaves, and any broken leaves need to be removed.

Another part of the sorting process that is more subjective is the separation of high-quality leaves from lesser quality; typically, bigger tea leaves are more prized than smaller leaves, and the separation of the different leaves happens in this step in the process.

The inspection can be done by humans or machines that can differentiate leaves from stems, broken leaves from complete etc. The mechanical means to do this can be accomplished by blowing air through the tea to separate the different parts, color inspection machines or even machines that can separate the leaves and other parts by means of their electric charge – who knew leaves and stems react differently to electrical charge?

Cutting.

The cutting process is not always carried out, but if it is, it is used to standardize the size of the tea. Tea that is uniform in size will tend to brew at the same speed; depending on the type of tea; uniform size of the tea adds to the ascetic appeal.

Pan-Firing.

Pan-firing is a secondary, optional, process in Japanese tea production, unlike in China, where it is the method used to stop oxidation. Pan firing (or roasting) is used in Japanese tea to impart a roasted flavor to the tea. Hojicha is an example of a very popular pan-fired tea that is classed as a green tea because of its primary processing steps, but in appearance is brown/red as a result of the pan firing. Pan-firing is sometimes carried out in large wok-like containers or, more usually now, in industrial machines specially designed for high-temperature, rapid roasting.

Blending.

This is an optional step but important, and a lot of time is devoted to the blending process if it is utilized.

Tea is a natural product, and its taste varies by numerous factors whilst it grows – sunshine varies from year to year, the rainfall amounts, the exact fertilizers used or the decisions that the farmer made during cultivation and harvesting.

Some tea is sold as single-source tea, and its taste will vary from year to year. A lot of tea sold currently is blended. The blending process is used to provide a consistent flavor that remains the same over many growing seasons. The blending process can also be used to mix spring tea with later teas to add characteristics of each season to the tea.

The blending process is a very skilled job; doing it well usually only comes with a lot of experience and in-depth knowledge of the tea-making process.

Grinding.

Powdered teas are ground during the Shiagecha process. The most famous of the ground tea in Japan is Matcha. Even today, much of the Matcha produced is ground on stone grinding wheels. Because of its popularity, one would assume that the wheels would now be of immense size to maximize the amount of tea that can be ground in a certain amount of time; in fact, the grinding wheels are typically only 12 inches or so in diameter and take almost a day to grind 30g of Matcha. Using larger wheels increases the temperature of the tea as it is processed, and this is not desirable. Matcha factories usually have many wheels, hundreds in some cases, all grinding small amounts of tea simultaneously. There are modern alternatives that use pressure and other techniques, but a lot, certainly, ceremonial grade Matcha is still ground on stone wheels – in a similar fashion to when tea first arrived in Japan centuries ago.

In our next and final installment of this series, we cover the steps involved in producing the types of Japanese Teas we enjoy.